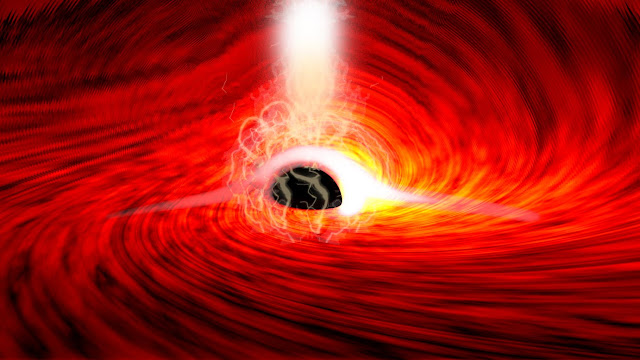

Watching X-rays flung out into the universe by the supermassive black hole

at the center of a galaxy 800 million light-years away, Stanford University

astrophysicist Dan Wilkins noticed an intriguing pattern. He observed a

series of bright flares of X-rays - exciting, but not unprecedented - and

then, the telescopes recorded something unexpected: additional flashes of

X-rays that were smaller, later and of different “colors” than the bright

flares.

According to theory, these luminous echoes were consistent with X-rays

reflected from behind the black hole - but even a basic understanding of

black holes tells us that is a strange place for light to come from.

“Any light that goes into that black hole doesn’t come out, so we shouldn’t

be able to see anything that’s behind the black hole,” said Wilkins, who is

a research scientist at the Kavli Institute for Particle Astrophysics and

Cosmology at Stanford and SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory. It is

another strange characteristic of the black hole, however, that makes this

observation possible. “The reason we can see that is because that black hole

is warping space, bending light and twisting magnetic fields around itself,”

Wilkins explained.

The strange discovery, detailed in a paper published today (July 28, 2021)

in Nature, is the first direct observation of light from behind a black hole

- a scenario that was predicted by Einstein’s theory of general relativity

but never confirmed, until now.

“Fifty years ago, when astrophysicists starting speculating about how the

magnetic field might behave close to a black hole, they had no idea that one

day we might have the techniques to observe this directly and see Einstein’s

general theory of relativity in action,” said Roger Blandford, a co-author

of the paper who is the Luke Blossom Professor in the School of Humanities

and Sciences and Stanford and SLAC professor of physics and particle

physics.

How to see a black hole

The original motivation behind this research was to learn more about a

mysterious feature of certain black holes, called a corona. Material falling

into a supermassive black hole powers the brightest continuous sources of

light in the universe, and as it does so, forms a corona around the black

hole. This light - which is X-ray light - can be analyzed to map and

characterize a black hole.

The leading theory for what a corona is starts with gas sliding into the

black hole where it superheats to millions of degrees. At that temperature,

electrons separate from atoms, creating a magnetized plasma. Caught up in

the powerful spin of the black hole, the magnetic field arcs so high above

the black hole, and twirls about itself so much, that it eventually breaks

altogether - a situation so reminiscent of what happens around our own Sun

that it borrowed the name “corona.”

“This magnetic field getting tied up and then snapping close to the black

hole heats everything around it and produces these high energy electrons

that then go on to produce the X-rays,” said Wilkins.

As Wilkins took a closer look to investigate the origin of the flares, he

saw a series of smaller flashes. These, the researchers determined, are the

same X-ray flares but reflected from the back of the disk - a first glimpse

at the far side of a black hole.

“I’ve been building theoretical predictions of how these echoes appear to us

for a few years,” said Wilkins. “I’d already seen them in the theory I’ve

been developing, so once I saw them in the telescope observations, I could

figure out the connection.”

Future observations

The mission to characterize and understand coronas continues and will

require more observation. Part of that future will be the European Space

Agency’s X-ray observatory, Athena (Advanced Telescope for High-ENergy

Astrophysics). As a member of the lab of Steve Allen, professor of physics

at Stanford and of particle physics and astrophysics at SLAC, Wilkins is

helping to develop part of the Wide Field Imager detector for Athena.

“It’s got a much bigger mirror than we’ve ever had on an X-ray telescope and

it’s going to let us get higher resolution looks in much shorter observation

times,” said Wilkins. “So, the picture we are starting to get from the data

at the moment is going to become much clearer with these new observatories.”

Reference:

Wilkins, D.R., Gallo, L.C., Costantini, E. et al. Light bending and X-ray

echoes from behind a supermassive black hole. Nature 595, 657-660

(2021). DOI:

10.1038/s41586-021-03667-0

Tags:

Space & Astrophysics