When a tissue experiences inflammation, its cells remember. Pinning proteins

to its genetic material at the height of inflammation, the cells bookmark

where they left off in their last tussle. Next exposure, inflammatory memory

kicks in. The cells draw from prior experience to respond more efficiently,

even to threats that they have not encountered before. Skin heals a wound

faster if it was previously exposed to an irritant, such as a toxin or

pathogen; immune cells can attack new viruses after a vaccine has taught

them to recognize just one virus.

Now, a new study in Cell Stem Cell describes the mechanism behind

inflammatory memory, also commonly referred to as trained immunity, and

suggests that the phenomenon may be universal across diverse cell

types.

“This is happening in natural killer cells, T cells, dendritic cells from

human skin, and epidermal stem cells in mice,” says Samantha B. Larsen, a

former graduate student in the laboratory of Elaine Fuchs at The Rockefeller

University. “The similarities in mechanism are striking, and may explain the

remitting and relapsing nature of chronic inflammatory disorders in

humans.”

Uncelebrated immunity

When thinking about our immune system, we default to specific immunity—that

cadre of T cells and B cells trained, by experience or vaccination, to

remember the specific contours of the last pathogen that broke into our

bodies. But there’s a less specific strategy available to many cells, known

as trained immunity. The impact is shorter-lived, but broader in scope.

Trained immunity allows cells to respond to entirely new threats by drawing

on general memories of inflammation.

Scientists have long suspected that even cells that are not traditionally

involved in the immune response have the rudimentary ability to remember

prior insults and learn from experience. The Fuchs lab drove this point home

in a 2017 study published in Nature by demonstrating that mouse skin that

had recovered from irritation healed 2.5 times faster than normal skin when

exposed to irritation at a later date.

One explanation, the Fuchs team proposed, could be epigenetic changes to the

skin cell genome itself. During inflammation, regions of DNA that are

usually tightly coiled around histone proteins unravel to transcribe a

genetic response to the attack. Even after the dust settles, a handful of

these memory domains remain open—and changed. Some of their associated

histones have been modified since the assault, and proteins known as

transcription factors have latched onto the exposed DNA. A once naïve cell

is now raring for its next fight.

But the molecular mechanism that explained this process, and how the cell

could use it to respond to types of inflammation and injury that it had

never seen before, remained a mystery.

Inside a memory domain

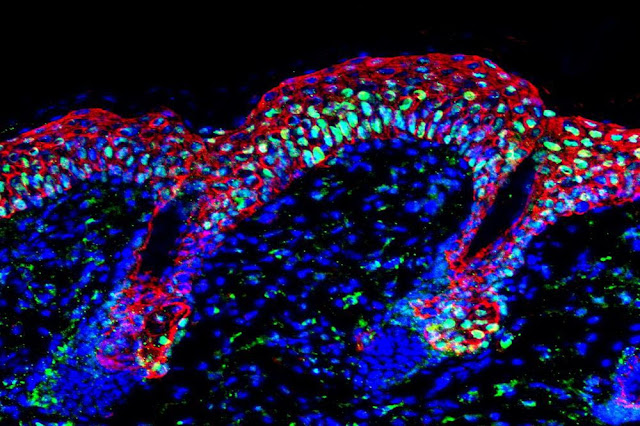

So the Fuchs lab once again exposed mice skin to irritants, and watched as

stem cells in the skin changed. “We focused on the regions in the genome

that become accessible during inflammation, and remain accessible

afterwards,” says Christopher Cowley, a graduate student in the Fuchs lab.

“We call these regions memory domains, and our goal was to explore the

factors that open them up, keep them open and reactivate them a second

time.”

They observed about 50,000 regions within the DNA of the stem cells that had

unraveled to respond to the threat, but a few months later only about 1,000

remained open and accessible, distinguishing themselves as memory domains.

Interestingly, many of these memory domains were the same regions that had

unraveled most prodigiously in the early days of skin inflammation.

The scientists dug deeper and discovered a two-step mechanism at the heart

of trained immunity. The process revolves around transcription factors,

proteins which govern the expression of genes, and hinges on the twin

transcription factors known as JUN and FOS.

The stimulus-specific STAT3 transcription factor responds first, deployed to

coordinate a genetic response to a particular genre of inflammation. This

protein hands the baton to JUN-FOS, which perches on the unspooled genetic

material to join the melee. The specific transcription factor that sounded

the original alarm will eventually return home; FOS will float away as the

tumult quiets down. But JUN stands sentinel, guarding the open memory domain

with a ragtag band of other transcription factors, waiting for its next

battle.

When irritation strikes again, JUN is ready. It rapidly recruits FOS back to

the memory domain, and the duo charges into the fray. This time, no specific

transcription factor is necessary to respond to a particular type of

inflammation and get the ball rolling. The system unilaterally activates in

response to virtually any stress—alacrity that may not always benefit the

rest of the body.

Better off forgotten

Trained immunity may sound like a boon to human health. Veteran immune cells

seem to produce broader immune responses; experienced skin cells should heal

faster when wounded.

But the same mechanism that keeps cells on high alert may instill a sort of

molecular paranoia in chronic inflammation disorders. When the Fuchs lab

examined data collected from patients who suffer from systemic sclerosis,

for instance, they found evidence that JUN may be sitting right on the

memory domains of affected cells, itching to incite an argument in response

to even the slightest disagreement.

“These arguments need not always be disagreeable, as animals benefit by

healing their wounds quickly and plants exposed to one pathogen are often

protected against others,” says Fuchs. “That said, chronic inflammatory

disorders may owe their painful existence to the ability of their cells to

remember, and to FOS and JUN, which respond universally to

stress.”

The scientists hope that shedding light on one possible cause of chronic

inflammatory disease may help researchers develop treatments for these

conditions. “The factors and pathways that we identify here could be

targeted, both in the initial disease stages and, later, during the

relapsing stages of disease,” says Cowley. Larsen adds: “Perhaps these

transcription factors could be used as a general target to inhibit the

recall of the memories that cause chronic inflammation.”

Reference:

“Establishment, maintenance, and recall of inflammatory memory” by Samantha

B. Larsen, Christopher J. Cowley, Sairaj M. Sajjath, Douglas Barrows, Yihao

Yang, Thomas S. Carroll and Elaine Fuchs, 27 July 2021, Cell Stem Cell.