New research published in Nature has revealed the solution to Jupiter's

'energy crisis', which has puzzled astronomers for decades.

Space scientists at the University of Leicester worked with colleagues from

the Japanese Space Agency (JAXA), Boston University, NASA's Goddard Space

Flight Center and the National Institute of Information and Communications

Technology (NICT) to reveal the mechanism behind Jupiter's atmospheric

heating.

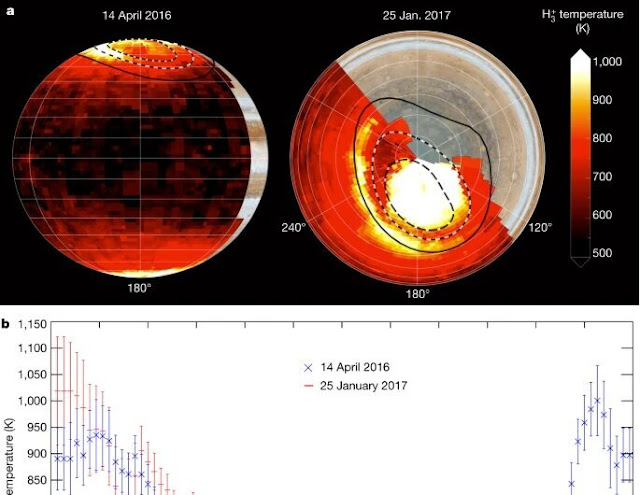

Now, using data from the Keck Observatory in Hawai'i, astronomers have

created the most-detailed yet global map of the gas giant's upper

atmosphere, confirming for the first time that Jupiter's powerful aurorae

are responsible for delivering planet-wide heating.

Dr. James O'Donoghue is a researcher at JAXA and completed his Ph.D. at

Leicester, and is lead author for the research paper. He said:

"We first began trying to create a global heat map of Jupiter's uppermost

atmosphere at the University of Leicester. The signal was not bright enough

to reveal anything outside of Jupiter's polar regions at the time, but with

the lessons learned from that work we managed to secure time on one of the

largest, most competitive telescopes on Earth some years later.

"Using the Keck telescope we produced temperature maps of extraordinary

detail. We found that temperatures start very high within the aurora, as

expected from previous work, but now we could observe that Jupiter's aurora,

despite taking up less than 10% of the area of the planet, appear to be

heating the whole thing.

"This research started in Leicester and carried on at Boston University and

NASA before ending at JAXA in Japan. Collaborators from each continent

working together made this study successful, combined with data from NASA's

Juno spacecraft in orbit around Jupiter and JAXA's Hisaki spacecraft, an

observatory in space."

Dr. Tom Stallard and Dr. Henrik Melin are both part of the School of Physics

and Astronomy at the University of Leicester. Dr. Stallard added:

"There has been a very long-standing puzzle in the thin atmosphere at the

top of every Giant Planet within our solar system. With every Jupiter space

mission, along with ground-based observations, over the past 50 years, we

have consistently measured the equatorial temperatures as being much too

hot.

"This 'energy crisis' has been a long standing issue—do the models fail to

properly model how heat flows from the aurora, or is there some other

unknown heat source near the equator?

"This paper describes how we have mapped this region in unprecedented detail

and have shown that, at Jupiter, the equatorial heating is directly

associated with auroral heating."

Aurorae occur when charged particles are caught in a planet's magnetic

field. These spiral along the field lines towards the planet's magnetic

poles, striking atoms and molecules in the atmosphere to release light and

energy.

On Earth, this leads to the characteristic light show that forms the Aurora

Borealis and Australis. At Jupiter, the material spewing from its volcanic

moon, Io, leads to the most powerful aurora in the Solar System and enormous

heating in the polar regions of the planet.

Although the Jovian aurorae have long been a prime candidate for heating the

planet's atmosphere, observations have previously been unable to confirm or

deny this until now.

Previous maps of the upper atmospheric temperature were formed using images

consisting of only several pixels. This is not enough resolution to see how

the temperature might be changed across the planet, providing few clues as

to the origin of the extra heat.

Researchers created five maps of the atmospheric temperature at different

spatial resolutions, with the highest resolution map showing an average

temperature measurement for squares two degrees longitude 'high' by two

degrees latitude 'wide'.

The team scoured more than 10,000 individual data points, only mapping

points with an uncertainty of less than five per cent.

Models of the atmospheres of gas giants suggest that they work like a giant

refrigerator, with heat energy drawn from the equator towards the pole, and

deposited in the lower atmosphere in these pole regions.

These new findings suggest that fast-changing aurorae may drive waves of

energy against this poleward flow, allowing heat to reach the equator.

Observations also showed a region of localized heating in the sub-auroral

region that could be interpreted as a limited wave of heat propagating

equatorward, which could be interpreted as evidence of the process driving

heat transfer.

Planetary research at the University of Leicester spans the breadth of

Jovian system, from the planet's magnetosphere and atmosphere, out to its

diverse collection of satellites.

Reference:

O'Donoghue, J. et al, Global upper-atmospheric heating on Jupiter by the

polar aurorae, Nature (2021).

DOI: 10.1038/s41586-021-03706-w

Tags:

Space & Astrophysics