The concept was until now purely theoretical. First predicted in 1934 by

Eugene Wigner, this structure - commonly referred to as the “Wigner crystal” -

would be made up exclusively of electrons, positioned in such a way that they

do not repel each other and remain stable. This is the first time that

scientists have created and managed to image such a crystal.

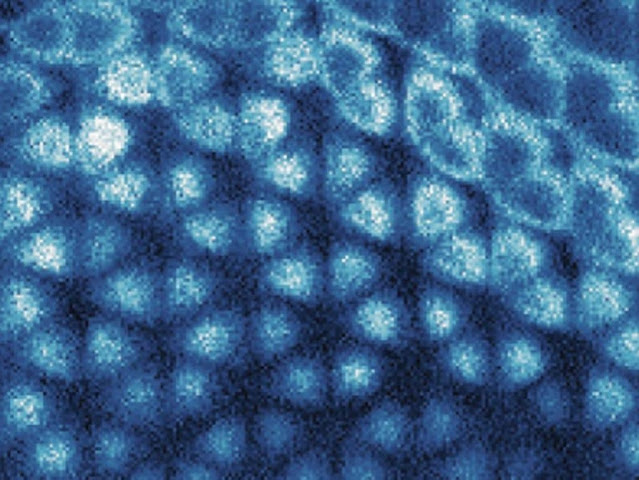

If the conditions are just right, some of the electrons inside a material

will arrange themselves into a tidy honeycomb pattern — like a solid within

a solid. Physicists have now directly imaged these ‘Wigner crystals’, named

after the Hungarian-born theorist Eugene Wigner, who first imagined them

almost 90 years ago.

Researchers had convincingly created Wigner crystals and measured their

properties before, but this is the first time that anyone has actually taken

a snapshot of the patterns, says study co-author Feng Wang, a physicist at

the University of California, Berkeley. “If you say you have an electron

crystal, show me the crystal,” he says. The results were published on 29

September in Nature.

A structure conducive to the appearance of the phenomenon

To create the Wigner crystals, Wang’s team built a device containing

atom-thin layers of two similar semiconductors: tungsten disulfide and

tungsten diselenide. The team then used an electric field to tune the

density of the electrons that moved freely along the interface between the

two layers.

In ordinary materials, electrons zoom around too quickly to be significantly

affected by the repulsion between their negative charges. But Wigner

predicted that if electrons travelled slowly enough, that repulsion would

begin to dominate their behaviour. The electrons would then find

arrangements that minimize their total energy, such as a honeycomb pattern.

So Wang and his colleagues slowed the electrons in their device by cooling

it to just a few degrees above absolute zero.

A mismatch between the two layers in the device also helped the electrons to

form Wigner crystals. The atoms in each of the two semiconductor layers are

slightly different distances apart, so pairing them together creates a

honeycomb ‘moiré pattern’, similar to that seen when overlaying two grids.

That repeating pattern created regions of slightly lower energy, which

helped the electrons settle down.

Images obtained using a carbon sheet

The team used a scanning tunnelling microscope (STM) to see this Wigner

crystal. In an STM, a metal tip hovers above the surface of a sample, and a

voltage causes electrons to jump down from the tip, creating an electric

current. As the tip moves across the surface, the changing intensity of the

current reveals the location of electrons in the sample.

Initial attempts to image the Wigner crystal by applying the STM directly on

the double-layer device were unsuccessful, Wang says, because the current

destroyed the fragile Wigner arrangements. So the team added a layer of

graphene, a single-atom sheet of carbon, on top. The presence of the Wigner

crystal slightly changed the electron structure of the graphene directly

above, which was then picked up by the STM. The images clearly show the neat

arrangement of the underlying Wigner electrons. As expected, consecutive

electrons in the Wigner crystal are nearly 100 times farther apart than are

the atoms in the semiconductor device’s actual crystals.

“I think that’s a great advancement, being able to perform STM on this

system,” says Carmen Rubio Verdú, a physicist at Columbia University in New

York City. She adds that the same graphene-based method will enable STM

studies of a number of other interesting physical phenomena beyond Wigner

crystals. Kin Fai Mak, a physicist at Cornell University in Ithaca, New

York, agrees. “The technique is non-invasive to the state you want to probe.

To me, it is a very clever idea.”

Reference:

Li, H., Li, S., Regan, E.C. et al. Imaging two-dimensional generalized Wigner

crystals. Nature 597, 650-654 (2021).

DOI: 10.1038/s41586-021-03874-9

Tags:

Physics