Lightspeed is the fastest velocity in the universe. Except when it isn't.

Anyone who's seen a prism split white light into a rainbow has witnessed how

material properties can influence the behavior of quantum objects: in this

case, the speed at which light propagates.

Electrons also behave differently in materials than they do in free space,

and understanding how is critical for scientists studying material

properties and engineers looking to develop new technologies. "An electron's

wave nature is very particular. And if you want to design devices in the

future that take advantage of this quantum mechanical nature, you need to

know those wavefunctions really well," explained co-author Joe Costello, a

UC Santa Barbara graduate student in condensed matter physics.

In a new paper, co-lead authors Costello, Seamus O'Hara and Qile Wu and

their collaborators developed a method to calculate this wave nature, called

a Bloch wavefunction, from physical measurements. "This is the first time

that there's been experimental reconstruction of a Bloch wavefunction," said

senior author Mark Sherwin, a professor of condensed matter physics at UC

Santa Barbara. The team's findings appear in the journal Nature, coming out

more than 90 years after Felix Bloch first described the behavior of

electrons in crystalline solids.

Like all matter, electrons can behave as particles and waves. Their

wave-like properties are described by mathematical objects called

wavefunctions. These functions have both real and imaginary components,

making them what mathematicians call "complex" functions. As such, the value

of an electron's Bloch wavefunction isn't directly measurable; however,

properties related to it can be directly observed.

Understanding Bloch wavefunctions is crucial to designing the devices

engineers have envisioned for the future, Sherwin said. The challenge has

been that, because of inevitable randomness in a material, the electrons get

bumped around and their wavefunctions scatter, as O'Hara explained. This

happens extremely quickly, on the order of a hundred femtoseconds (less than

one millionth of one millionth of a second). This has prevented researchers

from getting an accurate enough measurement of the electron's wavelike

properties in a material itself to reconstruct the Bloch wavefunction.

Fortunately, the Sherwin group was the right set of people, with the right

set of equipment, to tackle this challenge.

The researchers used a simple material, gallium arsenide, to conduct their

experiment. All of the electrons in the material are initially stuck in

bonds between Ga and As atoms. Using a low intensity, high frequency

infrared laser, they excited electrons in the material. This extra energy

frees some electrons from these bonds, making them more mobile. Each freed

electron leaves behind a positively charged "hole," a bit like a bubble in

water. In gallium arsenide, there are two kinds of holes, "heavy" holes and

"light" holes, which behave like particles with different masses, Sherwin

explained. This slight difference was critical later on.

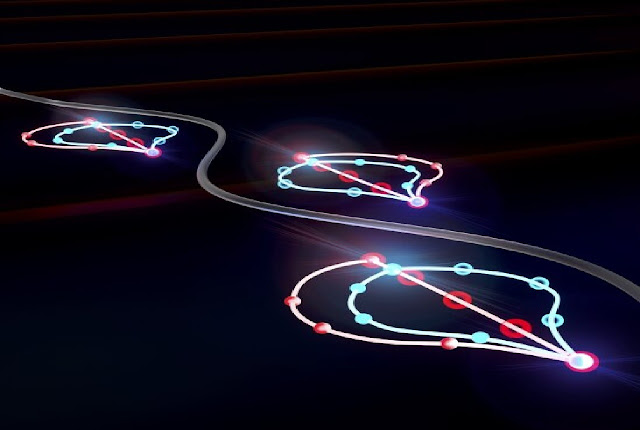

All this time, a powerful terahertz laser was creating an oscillating

electric field within the material that could accelerate these newly

unfettered charges. If the mobile electrons and holes were created at the

right time, they would accelerate away from each other, slow, stop, then

speed toward each other and recombine. At this point, they would emit a

pulse of light, called a sideband, with a characteristic energy. This

sideband emission encoded information about the quantum wavefunctions

including their phases, or how offset the waves were from each other.

Because the light and heavy holes accelerated at different rates in the

terahertz laser field, their Bloch wavefunctions acquired different quantum

phases before they recombined with the electrons. As a result, their

wavefunctions interfered with each other to produce the final emission

measured by the apparatus. This interference also dictated the polarization

of the final sideband, which could be circular or elliptical even though the

polarization of both lasers was linear.

It's the polarization that connects the experimental data to the quantum

theory, which was expounded upon by postdoctoral researcher Qile Wu. Qile's

theory has only one free parameter, a real-valued number that connects the

theory to the experimental data. "So we have a very simple relation that

connects the fundamental quantum mechanical theory to the real-world

experiment," Wu said.

"Qile's parameter fully describes the Bloch wavefunctions of the hole we

create in the gallium arsenide," explained co-first author Seamus O'Hara, a

doctoral student in the Sherwin group. The team can acquire this by

measuring the sideband polarization and then reconstruct the wavefunctions,

which vary based on the angle at which the hole is propagating in the

crystal. "Qile's elegant theory connects the parameterized Bloch

wavefunctions to the type of light we should be observing experimentally."

"The reason the Bloch wavefunctions are important," Sherwin added, "is

because, for almost any calculation you want to do involving the holes, you

need to know the Bloch wavefunction."

Currently scientists and engineers have to rely on theories with many

poorly-known parameters. "So, if we can accurately reconstruct Bloch

wavefunctions in a variety of materials, then that will inform the design

and engineering of all kinds of useful and interesting things like laser,

detectors, and even some quantum computing architectures," Sherwin said.

This achievement is the result of over a decade of work, combined with a

motivated team and the right equipment. A meeting between Sherwin and Renbao

Liu, at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, at a conference in 2009

precipitated this research project. "It's not like we set out 10 years ago

to measure Bloch wavefunctions," he said; "the possibility emerged over the

course of the last decade."

Sherwin realized that the unique, building-sized UC Santa Barbara

Free-Electron Lasers could provide the strong terahertz electric fields

necessary to accelerate and collide electrons and holes, while at the same

time possessing a very precisely tunable frequency.

The team didn't initially understand their data, and it took a while to

recognize that the sideband polarization was the key to reconstructing the

wavefunctions. "We scratched our heads over that for a couple of years,"

said Sherwin, "and, with Qile's help, we eventually figured out that the

polarization was really telling us a lot."

Now that they've validated the measurement of Bloch wavefunctions in a

material they are familiar with, the team is eager to apply their technique

to novel materials and more exotic quasiparticles. "Our hope is that we get

some interest from groups with exciting new materials who want to learn more

about the Bloch wavefunction," Costello said.

Reference:

J. B. Costello et al, Reconstruction of Bloch wavefunctions of holes in a

semiconductor, Nature (2021).

DOI: 10.1038/s41586-021-03940-2

Tags:

Physics